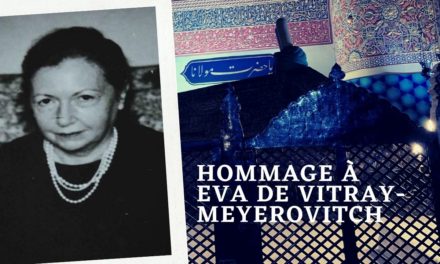

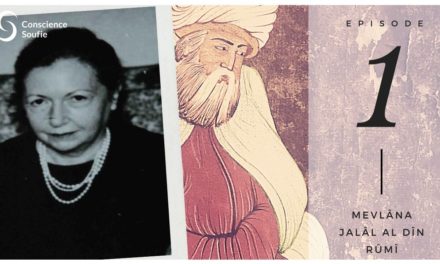

To the French audience, Eva de Vitray-Meyerovitch’s name will remain for ever associated to Rûmî’s name.

Eva de Vitray-Meyerovitch was born in 1909 in an aristocratic and very pious French Christian family. During her strict childhood in France, Eva began challenging the assumptions of her surroundings, and questioning received ideas at her parochial Catholic grade school where passive submission was often expected. She admired her Scottish Protestant grandmother for her puritan honesty, her insistence on telling the truth despite the difficulties that might entail. This grandmother converted to Roman Catholicism to marry her husband. Her granddaughter was in a way to follow in her footsteps. Eva did not hesitate, for example, to marry a Frenchman of Russian Jewish origin, because she was aware of the underlying spiritual connections between the religions. After her marriage to this Mr. Meyerovitch, she had to escape from Paris occupied by the Nazi troops, in 1940.

After the war, in the early 1950s, her life as a director of research was changed abruptly by the gift from a former Indian classmate, who returned to France from Pakistan. This gift was a book by Mohammad Iqbal, the famous twentieth-century Islamic philosopher and poet, and this book was the nice The Reconstruction of Religious Thought in Islam. Iqbal’s prose combined lucidity and ecstasy, touching the heart of this intellectual and sensitive woman. In this book, Iqbal was quoting a lot Rumi. Eva got immediately fascinated by this great soul. So she threw herself into translating Iqbal’s The Reconstruction of Religious Thought in Islam from English into French, and then she plunged into studying Persian language in order to be able to read Rûmî’s works in their original language. At first, she didn’t know that she was to devote her life to his works…

When she discovered Iqbal and Rumi, Eva de Vitray-Meyerovitch was, as a true disciple, ready to receive their teachings. Actually, she has got a keen mind well formed by years studying a lot of matters. She has been studying Christian theology at the prestigious French Sorbonne for three years, Greek philosophy (her PhD or doctoral thesis was on Plato) and Greek ancient language, Latin language, history, law and psychiatry. Her interest in different areas of the science, her interdisciplinarity and her way of dealing with various subjects was just fascinating.

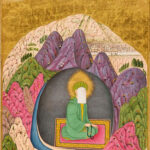

Eva de Vitray-Meyerovitch was a person absorbed by the inner quest for reality, and what is noteworthy in her itinerary is that her personal life and commitment were strongly linked with her intellectual investigations. They were directly inscribed into their logic. Of course, Rûmî became her spiritual mentor, just as if he took her hand and led her to the Muslim path. So she converted to Islam and until her death she used to fervently practice all the Islamic pillars and also Sufism.

She could easily have remained what she already was, a Roman Catholic scholar fond of Islamic mysticism. Her world, however, has been chocked by the Algerian struggle for independence. In Algeria, a minority of European colonizers denied the nationality of the overwhelmingly Muslim population, claiming the entire country was an integral part of France.

After her husband’s death, Eva chose the difficult path of becoming Muslim, siding with a civilization many of her compatriots considered inferior. She stood up for what she knew to be a far more demanding journey. She did not reject Judaism or Christianity, the roots of her own cultural frame of reference, but she found in Islam a path that encompassed these traditions. She entered Islam without renouncing or denying anything of her past, and she said that when she discovered Islam it was like “a return to her homeland” [1]. So she experienced personally Islam as Dîn al-Fitra, the religion of the pure and original nature of mankind. In a similar way, another great French Sufi, the metaphysician writer René Guénon (d. 1951), said he could not be converted to anything, because Islam should be assumed as an evidence and as a reminder of the previous revelations. As for Eva, we must add that her transition from Christianity to Islam should be understood by the prominent role granted to Jesus in the Islamic tradition and especially in Sufism [2]. Her Islamic name was, as expected, Hawwa, which is the exact translation of her Christian name.

By her conversion, Eva paid the price of rejection within her own society, by many friends, colleagues and family. She also had to deal with qualified acceptance by the community she chose to embrace, by those who treat the convert as lesser in stature, knowledge and authenticity.

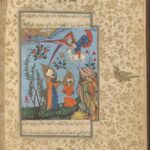

Moved by tenacious enthusiasm for the beauty of Rumi’s work, Eva de Vitray-Meyerovitch studied and translated into French his major books. Sufism has found its widest introduction in contemporary western society via Rumi’s spontaneous teachings. Many modern writers and translators have succeeded to convey the depth and scope of his insight, and the intensity of his love for God and for humanity, to those who do not have the good fortune to be able to read his words in Persian. Coleman Barks’ contemporary English renderings, Eva’s translations into French, Annemarie Schimmel’s work in German, and the efforts of many others, popular and academic, have made his inspiration accessible to millions. Now in France, Leili Anvar-Chenderoff comes to us with new translations of the poems of Rumi [3].

Eva had about thirty books about Sufism and Rumi to her credit when she started translating the 50,000 verses of the Mathnawi into French, which required from her some ten years of a persevering work [4]. “I have been working so much !”, she said after the publication of this monument of 1100 pages. Her last book was on Prayer in Islam; she dictated it because she was too weak to write it [5]. She also wrote an important and noticing book about Rumi’s town, Kunya, where she came a lot of times. This shows that for Eva, Turkey became her second homeland. Turkish authorities even used to qualify her of ‘Citizen of Honour’, and she received the title of “Doctor Honoris Causa” from Selçuk University for the invaluable services she rendered to Rumi and Turkish culture. In Islam, l’autre visage, book which took the form of an interview, Eva says that she felt at home neither in Paris nor nowhere else, but only in Turkey, and especially in Kunya [6]. The English translation of this book is to be soon published by Fons Vitae in the USA with this title: Towards the Heart of Islam: A Woman’s Approach [7].

Eva also lived in Egypt for six years, teaching philosophy at al-Azhar University as a representative of the CNRS, the French Scientific Research Center, and I personally got in touch in Cairo with her friends. She also travelled all over the world for giving many lectures on Islam and Sufism.

In Islam, l’autre visage, or Towards the Heart of Islam: A Woman’s Approach, Eva de Vitray makes us feel the internal connections which appear in spiritual life, through many anecdotes from her pilgrimage to Mecca, teaching at al-Azhar in Cairo, praying with a group of men in Algeria who fought to win their independence from her country, and through some relevant verses of Rumi. She also tells us how she devoted most of her life to explaining Rumi’s thought and translating his works. For her, the transmission of his universal message was truly urgent [8].

Through the centuries, Rumi has been the real spiritual master of Eva [9], but she took the Sufi initiation path from the Moroccan shaykh Hamza Butchichi, who is still alive. The first time he received her, he said: “Rumi is here !”, showing with his finger the place of his heart, and Eva collapsed into tears. Eva was also very linked with Khaled Bentounes, the shaykh of the tarîqa ‘Alawiyya, who, as Rumi, emphasizes on universal love [10]. Living in France, he was closer to her from the cultural point of view. After I became Muslim in 1984, I asked Eva’s advice about choosing an initiation Sufi path (tarîqa), and she sent me firstly to the ‘Alawiyya in Paris.

Eva de Vitray-Meyerovitch is among the few persons who lived with such a happiness between the East and the West, and who have been bridges between both cultures. We can quote among others Najm ed-din Bammate, Martin Lings, S.H. Nasr, Anne-Marie Schimmel, and some great orientalists like Louis Massignon or Henry Corbin who have been pioneers in the encounter between Islam and the West. The books and articles that Eva produced are our shared heritage today. She is well known especially in French-speaking countries. Her path, a woman’s journey to the heart, reflects the epic hero’s travel to distant lands, facing challenges from within and from without. “From her struggles, she brought back to us gifts of insight, treasures from the East, for a world in sore need of mutual respect and understanding. Her life of surrender to a higher purpose is a testimony of determination to transcend the fear of that which is different, in order to discover the encompassing love that connects us in all our rich diversity [11]”. Eva died in Paris on the 24 of July 1999.

[1] Islam, l’autre visage, Albin wichel, Paris, 1995, p. 52.

[2] Quoted from Fawzi Skalli.

[3] See for exemple Rûmî – La religion de l’amour, Paris, 2004.

[4] Mathnawi – La Quête de l’Absolu, Monaco, éd. du Rocher, 1990.

[5] La Prière en Islam, Albin Michel, Paris, 1998.

[6] Islam, l’autre visage, op. cit., p. 52.

[7] Translation by Cathryn Goddard (Cairo).

[8] Ibid., p. 69.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Ibid., p. 117, 119.

[11] See the Preface of Shaykh Khaled Bentounès (France) to Towards the Heart of Islam: A Woman’s Approach.

Bibliographie d’Eva de Vitray-Meyerovitch

Bibliographie essentielle :

- Mystique et Poésie en Islam, éd. Desclée de Brouwer, 1972.

- Rûmî et le Soufisme, éd. du Seuil, 1977, réédité en 2005, collection Points Sagesses. Ouvrage traduit en anglais, roumain, portugais, bosniaque, tchèque et turc.

- Anthologie du Soufisme, éd. Sindbad, 1978, plusieurs rééditions, Albin Michel. Ouvrage traduit en italien.

- Jésus dans la Tradition Soufie, co-écrit avec Faouzi Skali, éd. de l’Ouvert, 1985, réédité et complété en 2004, Albin Michel. Ouvrage traduit en italien, en espagnol et en catalan.

- Konya ou la Danse Cosmique, éd. Renard, 1990. Ouvrage traduit en turc.

- Islam, l’autre Visage, éd. Albin Michel, 1995. Ouvrage traduit en espagnol, en anglais et en turc.

- La Prière en Islam, éd. Albin Michel, 1998, Albin Michel. Ouvrage traduit en italien et en turc. (son dernier ouvrage).

Traductions du persan

- Le Livre de l’Eternité, de Muhammad Iqbal, avec de la collaboration de Mohammed Mokri,éd. Albin Michel, 1962.

- Le Livre du Dedans, de Jalâl ud Dîn Rûmî, éd. Sindbad, 1975, plusieurs rééditions, Albin Michel, coll. Spiritualités vivantes. Ouvrage traduit en italien et en espagnol.

- Maître et Disciple, de Sultan Valad, éd. Sindbad, 1982.

- Mathnawî : La Quête de l’Absolu, de Jalâl ud Dîn Rûmî, avec de la collaboration de Jamshid Murtazavi, éd. du Rocher, 1990.

- Les Quatrains de Rûmi, de Jalâl ud Dîn Rûmî, avec de la collaboration de Jamshid Murtazavi, Albin Michel, 2000.

- La Roseraie du Mystère, de Mahmud Shabestari, avec de la collaboration de Jamshid Murtazavi, éd. Sindbad, 1991.

Traductions de l’anglais

- Reconstruire la Pensée Religieuse de l’Islam, de Muhammad Iqbal, éd. Adrien-Maisonneuve, 1955, réédité en 1996, éd. du Rocher / UNESCO.

- La Métaphysique en Perse, de Muhammad Iqbal, éd. Sindbad, 1980.